BBC compares Nelson Mandela to Jesus Christ

- Posted on

- Comment

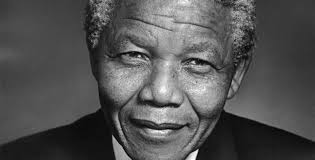

Sooner or later, it had to come. Over the weekend, the BBC presenter Evan Davis suggested that the late Nelson Mandela should be ranked alongside Jesus Christ in the pantheon of virtue.

Sooner or later, it had to come. Over the weekend, the BBC presenter Evan Davis suggested that the late Nelson Mandela should be ranked alongside Jesus Christ in the pantheon of virtue.

Admittedly, this came in the form of a question — to Jimmy Carter. The former U.S. president is also a Baptist minister, so he emphatically dismissed the notion, pointing out — to avoid any further misunderstanding by Davis — that Jesus is ‘The Son of God, actually God himself’.

Mandela’s greatness is not in doubt. His ability to work with and, apparently, forgive those who incarcerated him for 27 years in appalling conditions does conform to behaviour we might characterise as saintly.

He also had a radiant presence in public, one that entranced all who witnessed it. Yet political history should also warn us never to confuse the public and private man. They are very different — and Mandela was a spectacular example of this disjunction.

An important corrective to the process of instant canonisation was given by my old friend Richard Stengel, who worked for three years with Mandela on his autobiography, and whose superb memoir of the man was published in the Mail on Saturday.

We’ve kind of made him into Santa Claus. He wasn’t. He had tremendous anger and bitterness in his heart,’ Stengel said. ‘What made him such a fantastic and astonishing politician was that he never let anyone see that.’

The word ‘politician’ is almost a pejorative term, but Mandela was the consummate politician. Such people tend to have an instrumental view of humans: if they are useful, or necessary for the wider purpose, then devastating charm is deployed. If they are not useful, then the beam of light is switched off.

Thus, recalls Stengel (whose eldest son is a godchild of Mandela): ‘He was warm with strangers and cool with intimates. The smile was reserved for outsiders. I saw him often with his son, his daughters, his sisters; and the Nelson Mandela they knew appeared to be a stern and unsmiling fellow not terribly sympathetic to their problems.’

Of course, Mandela’s family life had been devastated by his long incarceration — and that was the doing of his oppressors, the apartheid regime; but even before then his multiple infidelities to his first wife, Evelyn, had created domestic havoc. As Evelyn remarked after the Secretary General of the South African Council of Churches stated that Mandela’s release was like the Second Coming of Christ: ‘How can a man who has committed adultery and left his wife and children be Christ? The whole world worships Nelson too much.’

And when he was at last a free man, his daughter Maki complained: ‘After he was released, he should have created some space for the family, for the children. We were ignored…

‘Children must learn to accept that sometimes they’re not really loved.’

Yet look at pictures of Mandela encountering children at a political rally and you see the man’s face glowing with what seems an inner warmth, almost luminous in its openness and apparent generosity of spirit.

Imagine how his own children, his own flesh and blood, must have felt when they saw such images, knowing they had never encountered the same affection — or at least the demonstration of it — bestowed on countless nameless babies offered up for presidential benediction.

This phenomenon, of public charm and private coldness, is a political commonplace, far from unique to Nelson Mandela. Indeed, an argument can be made that the more charming a politician seems in public, the more misanthropic or even cruel he will be in his life away from the scrutiny of the camera.

Many years ago precisely this point was made to me by my then personal assistant, Virginia Utley.

This acutely observant woman had previously worked as a secretary to various MPs; she told me that those at Westminster who had the most wonderful public image as caring and kind were dreadful employers, while the ones whose reputation was of a brutal and unfeeling personality were complete joys to work for.

I named this Utley’s law, as it seemed, on close examination, to have remarkable predictive accuracy.

It might have been most true of Margaret Thatcher. While harsh and abrasive in her public manner, it turned out that she behaved with enormous solicitude towards the secretaries and less exalted staff at Downing Street.

On the other hand, it was clear that her own home came emphatically second behind her political activities, so that when her career came to an abrupt end, there was no question of her wanting to spend more time with her family.

Yet we should not expect anything more from great men and women. The effort and energy involved in the political struggle at the highest level is almost beyond words to describe. It does require absolute dedication, a willingness to sacrifice the things which normal people would say are what makes life worth living.

Dailymail

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)