3 rules on how to survive the deadly ebola virus

- Posted on

- Comment

As West African nations try to stop the deadly Ebola virus from spreading, people living in the affected countries are nervous. In Sierra Leone, communities are keeping a close eye on the exact locations where the disease has emerged.

As West African nations try to stop the deadly Ebola virus from spreading, people living in the affected countries are nervous. In Sierra Leone, communities are keeping a close eye on the exact locations where the disease has emerged.

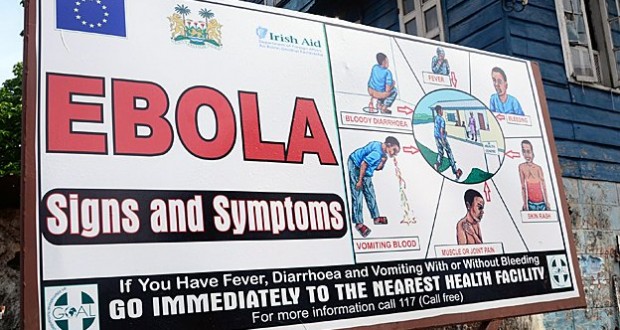

The posters are crudely drawn and graphic. There’s one pasted to the wall of the squat, concrete community centre in Kroo Bay, a slum in the centre of the capital Freetown, the kind of place where you can imagine disease spreading fast.

The houses are built of breeze block and have battered, rusting roofs. The spaces between them are piled with garbage, small children with no shoes tote yellow plastic jerry cans of water through the narrow lanes.

A pig lolls in the mud while her offspring snuffle in the filth.

Many Sierra Leoneans can’t read, so public information is often presented on large posters.

People in Freetown are nervous. They are desperate to keep the virus at bay, to keep it out in the provinces. They keep track of the numbers in the way they keep track of football scores.

“Ah, Port Loko,” said someone when I got back. “Four cases.”

I’d know from my colleagues immediately if they were talking about Ebola. It was in the tone of voice, the roll of the eyes, the uneasy laughter.

Then they would tell me that so and so had died and I would feel that rush of adrenaline triggered by sudden fear. One of my colleagues spent the whole day last week wearing a pair of blue rubber gloves.

People are frightened for two reasons. First and most importantly, because there’s no known vaccine, no cure; second, because of the ghastly physical reality of the disease, as portrayed in those lurid posters.

Yet these are people inured to disease. Consider, for example, their attitude to malaria, which kills thousands in Sierra Leone every year.

Not infrequently in the last few weeks I’ve encountered people complaining of a headache or a night of intense sweating.

They slide off to the hospital and reappear a day or two later with a bag full of drugs. They laugh it off.

“Oh yeah, there are so many mosquitoes at this time of year,” they say.

“But you sleep under a net, right?” Well, actually no, they don’t, even though sleeping under a treated net is the single most effective way to avoid getting bitten by a mosquito and being infected with malaria.

They see malaria as an occupational hazard but they see Ebola as a death sentence.

I spent an instructive couple of hours at the weekend with a woman from Finland. Eeva was once a midwife, but she’s just finished a five-week stint with a Red Cross team that has been going door to door in Kailahun province, the border region where Ebola first arrived in Sierra Leone.

She was on what’s known as a sensitisation mission, explaining to people exactly how the virus spreads and how to avoid it.

There are three simple rules, she told me.

Rule one: If you’ve got a headache or a fever, go to the health centre for a test. You can recover from Ebola if the infection is spotted early enough.

Rule two: If someone dies, don’t touch the body. It’s highly infectious. Don’t wipe the mouth, don’t close the eyes.

Rule three: Don’t eat bushmeat, the meat of wild animals.

The underlying message was this – Ebola is manageable. It’s deadly and frightening but if you follow the three rules and use a lot of soap and water, you probably won’t get sick. And if you do, even though the death rate is high, there are survivors.

I told Eeva she was a brave woman, but she shrugged the compliment off.

She said she’d had the opportunity to take two different jobs – one in Sierra Leone, the other in South Sudan, where there’s continuing fighting. “I told myself, I’m not going to South Sudan – I’ve got a family,” she said.

As I left Freetown on Sunday morning there was a last reminder of the Ebola spectre. Outside the airport building was a table and a couple of buckets. We all had to wash our hands in water that carried a strong whiff of chlorine.

My friend in the blue rubber gloves had jokingly asked me if I might have space for him in my suitcase.

I sympathise with his powerlessness; I had a plane ticket; he can only sit and wait. I hope the message that Ebola is both manageable and survivable gets through.

-BBC

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)