Twice caught doping, once facing a lifetime ban that was reduced first to eight years and then to four, he has long been the anti-poster boy for track and field – lacking any obvious remorse, humility left for others, a frequent swaggering reminder that cheats can still prosper should their legal team find the right angle to work.

Not all the rancour has made logical sense. Others at these World Championships have returned from suspensions. Russia is banned indefinitely for its 21st century take on state-sponsored doping. Only Gatlin was booed every time he took to the blocks, from heats on Friday morning to semi-finals on Saturday evening and then the final itself.

So it was that as he thrust his upper body across the finish line just after 21:45 BST – almost unnoticed in lane eight, outside the peripheral vision of Bolt in four and young American Christian Coleman in five – a wave of shock rolled around the packed slabs of supporters, turning to disbelief, to not wanting to accept what had just happened, to hoping something might suddenly be revealed to make it right.

Gatlin does not find charm easy to access. He slammed on the brakes, jumped to attention and put a single, admonishing finger to his lips, daring the crowd to mock him now.

Revenge, it seemed, was his – for the catcalls of the past two days, for those who considered him shot at 35, for the mess Bolt has made of his tilts at world and Olympic gold since he returned to competition an older and unapologetic man in 2010.

And then you heard the crowd respond again, first the thousands close to him on the top bend, then those all around the oval track.

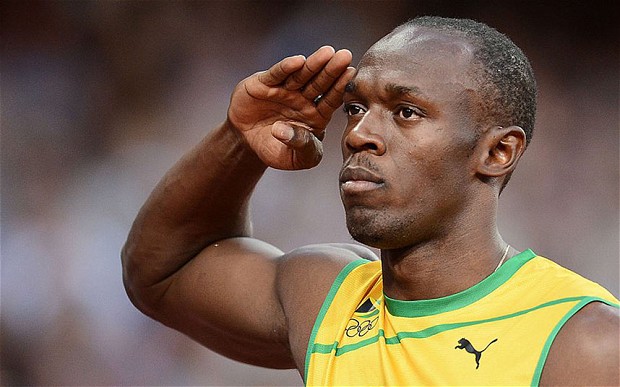

“Usain Bolt! Usain Bolt! Usain Bolt!”

This was Gatlin’s moment of triumph: unacknowledged, unwanted, first mocking and then being mocked in return.

The lap of honour? That went to Bolt. The first interview with the in-field presenter? Bolt. The one all the spectators ran down to trackside to touch and to photograph and to seize for selfies? Bolt.

A victory, but a pyrrhic one. A defeat, but one that was treated like a triumph.

The strangest of nights, and a strange truth: Gatlin may have deserved all of that – but he deserved this win too, in its technique and focus if not its ancestry.

In 2015, expected to beat an ailing Bolt at the last World Championships in Beijing. He had led with 15 metres to run only to over-stride with triumph in front of him and let the king cling on to his crown. Now, at an age when his youthful speed has leached away, he ran through the line as if nothing could touch him.

Bolt’s reaction to the gun was the slowest of anyone in the race. Five hundredths of a second ceded to Gatlin before a metre had been run, a hundredth more to Coleman.

When the chase came, the invisible bungee cord of old had been replaced by a rope. There was acceleration but no surge. The champion tightened, but not the American kid nor the compatriot 14 years his senior.

Gatlin finished in 9.92 seconds, Coleman in 9.94, Bolt in 9.95. Never before had the 30-year-old Jamaican run so slowly in a major final. In this same stadium, five golden summers ago, he had run 9.63. You can’t keep stopping the clock. One day it will stop you.

The World Championships have defined Bolt and given him a simple narrative.

Berlin 2009: his world record of 9.58, the greatest run of all. Daegu 2011: disqualified for a false start, his greatest disappointment. Beijing 2015: the defeat from nowhere of Gatlin, arguably his greatest miracle.

This was supposed to be the great finale. That the story was hijacked by a darker subplot will leave some feeling as if something sacred has been blemished, that same sense of sadness experienced by those who saw boxer Muhammad Ali beaten in 10 melancholic rounds by Trevor Berbick in his own concluding fight.

Yet sometimes perfection itself can become hard to understand when it seems to come so easy. In defeat, we can look back at all the glories of the past nine years and see that none were preordained and all claimed through an unprecedented blend of latent talent and unremitting hard work.

Bolt has done so much on the track that no other human has ever managed. That his last individual race revealed him to have a few mortal flaws after all should not undermine his status.

He talked of wanting to be remembered like Ali, like Pele. He will be.

Gatlin has his world title – but never will he win the same affection nor respect. An imperfect ending, but with its own little perfections too.

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)