From BBC: 6 things you should know about Ghana’s elections

- Posted on

- Comment

Ghanaians are going to the polls to elect a new president and parliament in a country seen as one of the most democratic in West Africa.

Eleven candidates are in the race to unseat President Nana Akufo-Addo, who is running for his second term.

His main challenger is his predecessor and 2016 opponent, John Dramani Mahama.

Youth unemployment, security concerns and effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy are among the top issues Ghanaians will consider when voting.

Here are six things to know about this election.

1. It’s déjà vu – again

The world has gone through so much uncertainty and surprises this year but Ghana’s presidential race is remarkably familiar.

The ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) candidate, Mr Akufo-Addo, 76, and his longtime rival, Mr Mahama, 62, of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), will slug it out for the presidency for a record third time. The two men first ran against each other in 2012.

In the first contest, Mr Mahama unexpectedly became his party’s candidate after then President John Evans Atta Mills died just five months before the presidential poll.

Mr Mahama, 62, went on to defeat Mr Akufo-Addo, 76, who had been tipped to win.

The results were challenged in court on grounds of electoral fraud but after eight months Ghana’s Supreme Court upheld Mr Mahama’s narrow victory.

Mr Akufo-Addo, however, got his revenge in 2016.

Mr Mahama told BBC Pidgin in a recent interview that an ailing economy, a power crisis that he resolved a little too late, and “fake news from opposition’s social media troll factory” led to his defeat four years ago.

But whatever happens, there will not be a fourth face-off between the two men – whoever wins will be ruled out of future elections after serving two terms.

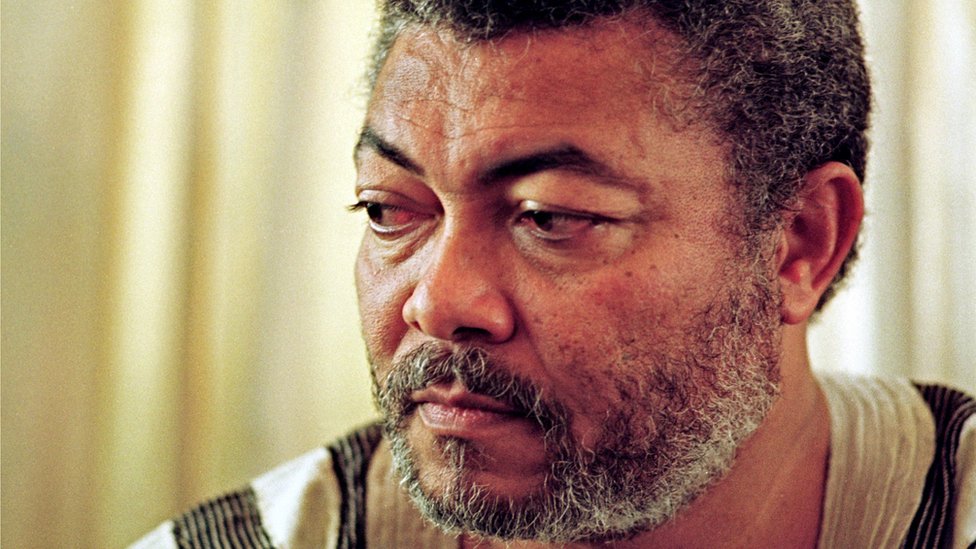

2. The Rawlings factor

This will be the first time since democracy was re-established in 1992 – after years of military rule – that an election will be held without the physical influence of the late former president Jerry Rawlings

The charismatic and popular leader, who oversaw the return of multiparty politics, died at the age of 73 at a hospital in the capital, Accra, on 12 November following a short illness.

Although Rawlings backed the ruling NPP in the 2016 election, political observers say Mr Mahama’s NDC, founded by Rawlings, stands to gain some form of sympathy vote.

Rawlings’ backing of Mr Akufo-Addo caused disaffection in the opposition party and cost it votes.

More than 80,000 NDC supporters in various constituencies across the Volta Region, the party’s stronghold, did not vote in the 2016 election, Mr Mahama told BBC Pidgin.

Prior to Rawlings’ death, the NDC had made efforts to mend its relationship with him and party officials now say they are confident that they will avoid of a repeat of the apathy four years ago.

But there could be a complication: Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings, the former president’s widow, is the presidential candidate of the National Democratic Party (NDP).

3. First election without ‘vigilante groups’

There is some sense of relief in the country that the elections will not be marred by clashes instigated by vigilantes hired by politicians.

A law passed last year with bipartisan support banned vigilantism making it punishable by a 10-year minimum jail term. The law has so far been a deterrence judging from events leading to the election.

The two main political parties had been guilty of hiring muscular young men with quasi-security training ostensibly to “secure the ballot.”

They instead built a reputation of using intimidation and violence against opponents.

4. Western Togoland separatism

However, one shadow hanging over the poll is the separatist groups that have intensified calls for independence from Ghana to form their own country – Western Togoland.

The calls for self-determination re-emerged in 2017 – after a hiatus of almost two decades – when two more militant splinter groups were formed.

In September, one of the new groups, the Western Togoland Restoration Front (WTRF), staged violent attacks for the first time in the history of the separatist movement.

It mounted roadblocks, attacked a police station, seized weapons and burnt down a bus terminal.

The government has deployed the military to the Volta Region ahead of the polls to thwart any attempt to disrupt the elections.

5. ‘Ecowas register’ cleaned

Ghana’s Electoral Commission compiled a new voter register ahead of the polls in an effort to remove foreign nationals suspected to have been added – earning the moniker “Ecowas register” – in reference to the West African regional bloc of which Ghana is a member.

In June, the military was deployed to opposition strongholds in the border towns in Volta Region ahead of the voter registration exercise to provide security.

The NDC accused the commission of attempting to disenfranchise people who have dual citizenship, particularly those of Ghanaian and Togolese extraction.

Electoral Commission Chairperson Jean Mensa denied the claims of prejudice against people from the Volta Region.

Two million more voters will be eligible to vote in Monday’s election compared to four years ago.

In 2016 Ghana’s electoral commission won plaudits around the world for overseeing a competent electoral process.

The authorities are aware of this reputation and will want to ensure they meet the expectations.

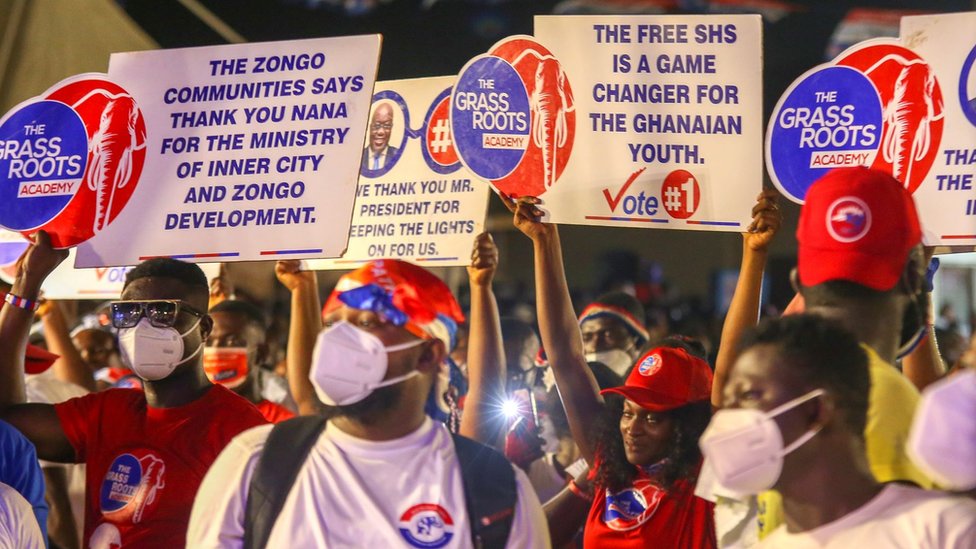

6. Campaigning amid Covid-19

The pandemic changed the way campaigns were conducted – a situation that has frustrated both politicians and the public.

Instead of the noisy, colourful and vibrant mass rallies, political parties have mostly used tweets, memes and videos on social media to sell their messages.

The main political parties have battled it out on Twitter and Facebook by posting and sharing counter-messages.

Radio, television and bulk text messages have also been used to campaign.

However, in the last days of campaigning, caution was thrown to the wind as politicians met crowds of voters. There is now concern that there could be a surge in coronavirus infections.

Ghana has reported more than 50,000 Covid-19 infections, with at least 300 people succumbing to the virus.

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)