Methane detected on Mars

- Posted on

- Comment

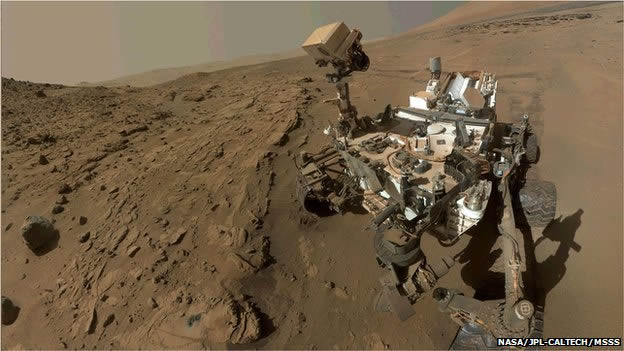

Nasa’s Curiosity rover has detected methane on Mars – a gas that could hint at past or present life on the planet.

Nasa’s Curiosity rover has detected methane on Mars – a gas that could hint at past or present life on the planet.

The robot sees very low-level amounts constantly in the background, but it also has monitored a number of short-lived spikes that are 10 times higher.

Methane on the Red Planet is intriguing because here on Earth, 95% of the gas comes from microbial organisms.

Researchers have hung on to the hope that the molecule’s signature at Mars might also indicate a life presence.

The Curiosity team cannot identify the source of its methane, but the leading candidate is underground stores that are periodically disturbed.

Curiosity scientist Sushil Atreya said it was possible that so-called clathrates were involved.

“These are molecular cages of water-ice in which methane gas is trapped. From time to time, these could be destabilised, perhaps by some mechanical or thermal stress, and the methane gas would be released to find its way up through cracks or fissures in the rock to enter the atmosphere,” the University of Michigan professor told BBC News.

He was reporting the discovery here at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting.

The question remains, of course, of how the methane (CH4) got into the clathrate stores in the first place.

It could have come from Martian bugs; it could also have come from a natural process, such as serpentinisation, which sees methane produced when water interacts with certain rock types.

At the moment, it is all speculation. But at least Curiosity has now made the detection.

Enriched samples

It was concerning that for many months the robot could not see a gas that was being observed by orbiting spacecraft at Mars and by telescopes at Earth.

People were beginning to wonder if the other sightings were reliable.

Curiosity is located in a deep bowl on Mars’ equator known as Gale Crater.

It has been sucking in Martian air and scanning its components since shortly after landing in August 2012.

For gases that have very low concentrations in the atmosphere, the robot can employ a special technique in which it expels the most abundant molecule – carbon dioxide – before analysing the sample.

This has the effect of enriching and amplifying any residual chemistry.

And in doing this for methane, Curiosity finds that there is a persistent signature of about 0.7 parts per billion by volume (ppbv).

“The background figure suggests there are about 5,000 tonnes of methane in the atmosphere,” said Dr Chris Webster, from Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who led the investigation.

“You can compare that with Earth where there are about 500 million tonnes. The concentration here at Earth is about 1,800 ppbv.”

Life’s preference

The spikes in methane that Curiosity saw occurred on four occasions during the course of a two-month period.

They varied between about 7 and 9 parts per billion by volume.

It is likely, the team says, that the gas is being released relatively nearby, either within the crater or just outside.

Curiosity’s weather station suggests it is blowing in from the north, from the direction of the crater rim.

One way to investigate whether the methane on Mars has a biological or a geological origin would be to study the types, or isotopes, of carbon atom in the gas.

On Earth, life favours a lighter version of the element (carbon-12), over a heavier one (carbon-13).

A high C-12 to C-13 ratio in ancient Earth rocks has been interpreted as evidence that biological activity existed on our world as much as four billion years ago.

If scientists could find similar evidence on Mars, it would be startling. But, sadly, the volumes of methane detected by Curiosity are simply too small to run this kind of experiment.

“If we had enriched our sample during one of the peaks, we might have had a shot at looking at these isotopes,” explained Dr Paul Mahaffy, the lead investigator on Curiosity’s Surface Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument, which did the measurements.

“I think there is still some hope. If the methane comes back, and we can enrich it, we’ll certainly be trying.”

Long quest

The other big Curiosity discovery announced here in San Francisco is that the rover has also confirmed the detection of organic (carbon-rich) compounds in the rock samples it has been drilling.

It is the first definitive detection of organics in surface materials at the Red Planet.

The SAM instrument saw evidence for chlorobenzine in the powered rock it pulled up from a mudstone slab dubbed Cumberland.

Chlorobenzine is a carbon ring with five hydrogen atoms and one chlorine atom attached.

The team cannot be sure if the chemical was specifically present in Cumberland or synthesised during the heating of analysis. But even if the latter is the case, the scientists seem confident the molecule would at the very least have been derived from larger carbon structures that were in place.

Once again, scientists are interested in seeing such organics because life as we know it can only exist if it has the capacity to trade in carbon molecules.

If they are not present then neither will there be any biology. However, just as with the methane detection, this does not of itself automatically point to life on Mars, now or in the past, because there are plenty of abiotic processes that will produce complex carbon structures as well.

“It’s a big day for us – it’s a kind of crowning moment of 10 years of hard work – where we report there is methane in the atmosphere and there are also organic molecules in abundance in the sub-surface,” commented Curiosity project scientist Prof John Grotzinger.

– BBC

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)