Four million people risk losing India citizenship

- Posted on

- Comment

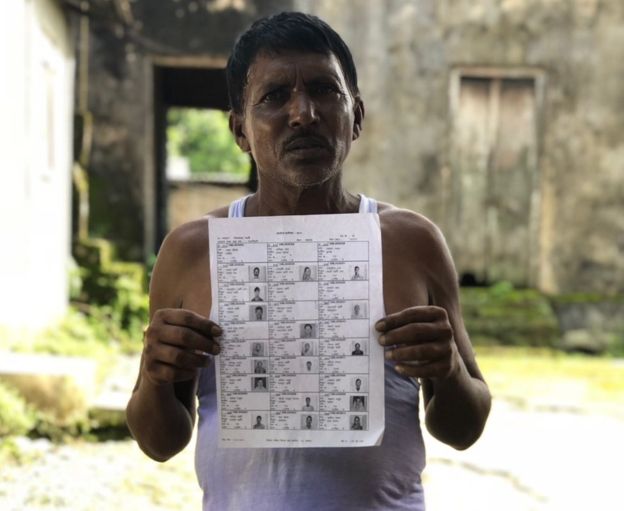

India has published a list which effectively strips about four million people in the north-eastern state of Assam of their citizenship.

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is a list of people who can prove they came to the state by 24 March 1971, a day before neighboring Bangladesh declared independence.

India says the process is needed to identify illegal Bangladeshi migrants.

But it has sparked fears of a witch hunt against Assam’s ethnic minorities.

Fearing violence, officials say that no-one will face immediate deportation.

They say that a lengthy appeal process will be available to all – even if it means millions of families will live in limbo until they get a final decision on their legal status.

Who is affected?

Millions of people fled to neighboring India after Bangladesh declared itself an independent country from Pakistan on 26 March 1971, sparking a bitter war. Many of the refugees settled in Assam.

Under the Assam Accord, an agreement signed by then PM Rajiv Gandhi in 1985, all those who cannot prove that they came to the north-eastern state before 24 March 1971 will be deleted from electoral rolls and expelled as they are not considered legitimate citizens.

More than 32 million people submitted documents to the NRC to prove they were citizens, but four million of them have been excluded from the published list.

Are Bengalis being targeted?

Activists say the NRC is now being used as a pretext for a two-pronged attack – by Hindu nationalists and Assamese hardliners – on the state’s Bengali community, a large portion of whom are Muslims.

Like Hasitun, many Bengalis live in the wetlands dotted along the Bramaputra river, moving around when water levels rise. Their paperwork, if it exists, is often inaccurate.

Officials claim illegal Bangladeshis are enmeshed in the Bengali population, often hiding in plain sight with forged papers – and a thorough examination of all documents is the only way to find them.

Many Bengalis – a linguistic minority in Assam – are worried they will be deported en masse.

Hasitun Nissa, who spoke to the BBC’s Joe Miller days before the list was published, said she had never known a home outside the state’s floodplains.

It is where the 47-year-old schoolteacher spent her childhood, where she studied, where she got married and where she had her four children.

She said her family arrived in India before 1971 but she expected to be stripped of her Indian citizenship and feared her land rights, voting rights, and freedom would be in peril.

But Bengali campaigner Nazrul Ali Ahmed is adamant that the NRC is serving another agenda entirely.

“It is nothing but a conspiracy to commit atrocities,” he told the BBC.

“They are openly threatening to get rid of Muslims, and what happened to the Rohingya in Myanmar, could happen to us here.”

Such alarming comparisons are dismissed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, which emphasizes that the NRC is an apolitical task, overseen by the country’s secular Supreme Court.

After human rights organizations began to express concern, the civil servant in charge of the NRC, Prateek Hajela, released a statement stressing that the law required him to make “no differentiation on the basis of religion or language” in determining citizenship.

But correspondents say the prime minister has never been shy of expressing his preference for Hindu Bangladeshi migrants, whom he says should be embraced by India.

Other “infiltrators”, Mr. Modi told a crowd in 2014, would be deported.

Indeed, a promotional song posted on Facebook by the NRC itself does little to calm the nerves of those worried about a Hindu nationalist witch hunt.

“A new revolution, to defeat the alien enemy, is beckoning,” a young woman sings, “bravely let us shield our motherland.”

Will there definitely be deportations?

Siddhartha Bhattacharya, Assam’s law minister and a member of the BJP, is in no doubt about the fate of those who have been rejected.

“Everyone will be given a right to prove their citizenship,” he told the BBC. “But if they fail to do so, well, the legal system will take its own course.”

That, Mr. Bhattacharya clarified, would mean expulsion from India.

At present, correspondents say, that seems little more than a threat aimed at whipping up Hindu support for the BJP ahead of elections.

No deportation procedures have been put in place, and Bangladesh, already burdened by the Rohingya crisis, has shown no sign of being open to accepting a raft of new refugees.

Nonetheless, campaigners like Samujjal Bhattacharyya say something must be done.

His organization, the All Assam Students’ Union, has been agitating for the expulsion of illegal Bangladeshis – regardless of their religion – for decades.

If deportations don’t happen, he says, “the illegal foreigner will intrude upon the corridor of power. We are not prepared to be second-class citizens”.

Hasitun Nissa takes such rhetoric seriously.

“We have never harmed Hindus. We can live peacefully side-by-side,” she says. “But I fear bad news will come.”

Source: BBC

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)