Working but starving; Informal jobs pay GH¢150 monthly

- Posted on

- Comment

The payment of low wages to employees in the informal sector in Accra and other parts of the country is making it difficult for them to lead decent lives.

The low wages make it difficult for that category of workers to live on their wages beyond two weeks.

Even some public sector workers find themselves in a similar circumstance.

Wages in the informal sector in the capital vary from as low as GH¢150 to about GH¢450 a month, according to Daily Graphic checks.

Kitchen assistants at chop bars, shop attendants, private car drivers, house helps, seamstresses, hairdressers, watchmen, food vendors and traders are stretched to the limit, yet they earn incomes below the minimum wage, which is currently pegged at GH¢9.68.

The minimum wage was increased to GH¢9.68 in July in 2017 and further increased on July 26, 2018, to GH¢10.65,

The new wage, which represents a 10 percent upward review, will take effect on January 1, 2019.

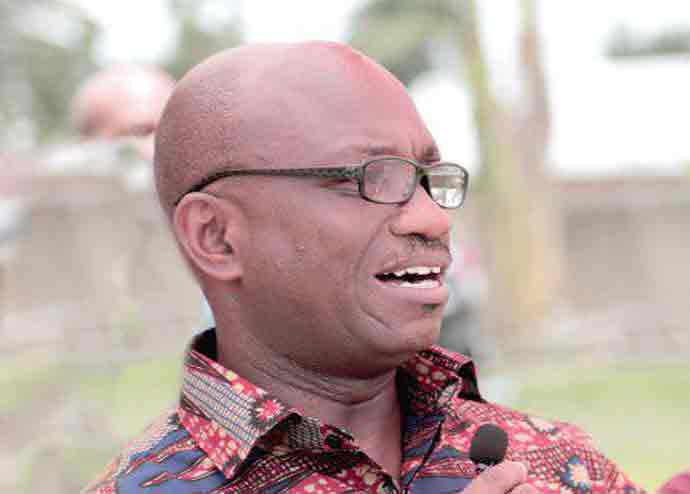

Ministry reacts

When contacted, a Deputy Minister of Employment and Labour Relations, Mr. Bright Wireko-Brobby, agreed that there were challenges with low remuneration, particularly in the informal sector.

He also acknowledged that there were challenges with employers adhering strictly to the payment of tiers two and three contributions for their employees, as required by the National Pensions Act.

He said the challenge was because the Labour Department lacked the adequate personnel to go round and enforce the law.

“The problem is with logistics for the Labour Department to go round to factories and other workplaces to ensure best practices in the labor value chain, including safety standards, maternity leave for women and pensions (tiers two and three),” he said.

He, however, said the ministry was working on getting more inspectors to do the field work, which would lead to the Attorney-General (A-G) prosecuting employers who paid their workers below the minimum wage or had not been paying pension contributions of their workers.

Supermarkets

The minimum wage is the least wage below which no employer pays a worker in Ghana.

However, there are many worrying stories on the streets and in the homes and shops in Accra, with some employers paying below the minimum wage and virtually nothing for a pension.

An encounter with some of the workers of major supermarkets and malls, including Melcom, Citydia, Palace, Game, and Koala, revealed that the workers were paid between GH¢400 and GH¢800 a month, depending on years of experience as salespersons.

More work, less pay

When Ms Sandra Osei was engaged by a chop bar operator as a kitchen assistant in a popular chop bar at Achimota, the owner promised to pay her GH¢300 monthly.

However, a month into the job, the owner decided to vary the agreement and paid her GH¢150 because she gave Sandra breakfast and lunch.

“Everyone knows that when you work in a chop bar, you eat from there; you don’t buy your food, but the owner decided that because we are eating from here, our daily wage should be reduced,” Sandra lamented.

Pointing at a large pot on a coal pot, she said: “I cook two of that every day and help prepare soup, all for the same pay. I can’t even save.

When you complain, she threatens to sack you. How do I pay rent, water and electricity bills, transport and other personal items from an amount like that? It is very difficult.”

Too many bills

Responding to the concerns, the chop bar owner, Ms. Mary Owusu-Ansah, said although the wages seemed low, her business tried as much as possible to reduce other financial pressures on employees by providing them two meals or sometimes three.

“I have eight employees and can’t pay beyond a certain amount, otherwise the business will collapse. We use a lot of water and electricity and the cost of food is not stable. If you add what they eat as part of the wages, it is a lot of money,” she said.

Other stories

Sandra’s story is not different from that of Aisha, a 21-year-old junior high school graduate who washes dishes for a food vendor at the Kwame Nkrumah Circle in Accra.

A typical day for her starts at 5 a.m. when she helps cart food, including plain rice, jollof, ampesi, and banku, to the roadside eatery.

She works until 6 p.m. or even later, depending on when the pots are emptied, and for the work that she does, she is paid GH¢10 a day.

The Maamobi resident works every day except Fridays.

She expressed the hope that she would be able to save enough to start an apprenticeship in hair braiding, but after almost two years of working, she is nowhere close to the GH¢2,500 she needs to start the three-year training.

Frowns

Deep in the belly of the central business district of Accra, a private car driver, Amankwa, opened a post office box and cleared the contents into a Manila envelope and then put it on the back seat of the vehicle.

When his phone rang, he frowned. The longer the person on the other end of the line spoke, the more Amankwa frowned.

When the call ended, he said: “That was my madam; she is sending me to Tema. I came to pick up her letters. I have already been to Kasoa to give money to masons and Winneba to deliver some items to her parents. From Tema, I may have to go to Pokuase, where she lives, to deliver clothes from her seamstress, before going to pick up her children from school at Dzorwulu. From there, I have to find my way home to Awoshie.”

“It is already 1 p.m. and I’m yet to have even breakfast. I do all these for GH¢300 a month,” the father of three added.

Even worse, he said, his boss had refused to pay his social security contribution and he had been asking for a pay rise in the last eight months but she had threatened to sack him.

“I spoke with someone who works at SSNIT and he asked me to come and file complaints, but the problem is that she will sack me immediately they call her. The only reason l keep doing this job is the welfare of my children and the occasional tips I get from our clients.

“Within a week and a half, the salary is gone. Were it not for my wife who helps a lot from her catering business, things would be very bad,” the 46-year-old former taxi driver said.

Too young to ask for more?

Not far from the Central Post Office works Joan (not real name) as a shop attendant who sells electrical appliances.

The 19-year-old’s monthly salary is GH¢200. She lives at James Town and recently completed senior high school.

“I walk to work, but I end up spending everything on lunch. I spend at least GH¢6 every day at lunch. I sometimes have to take money from my parents for the church. The salary is horrible, but it is better than sitting at home.

“Sometimes within two weeks, the salary is gone. My boss said after a three-month probation my salary would be raised, but it has been almost a year. Whenever I mention it, he says sales are low and even pisses me off by saying I’m too young to be asking for more money,” she said.

A nanny’s tale

Miriam was 17 years when she got her job as a maid at Achimota in Accra two years ago.

Being a nanny to three children aged nine, seven and three made her life miserable, she said.

She receives GH¢250 at the end of the month as a live-in house help. She cooks, washes dishes, prepares the children for school, as well as supervises their homework on weekdays.

“My madam is good. She helps me when she is home, but she has refused to increase the salary. She is always talking about surprising me when I decide to leave, but it is not fair. I have needs and also supports my two brothers who are in school,” she said.

Not good, but ok

Among the lot, the only person who has a different story is Michael A. Atamadi, a cashier at a cold store at the Makola Market.

The 34-year-old SHS graduate earns GH¢450 a month. He receives two kilograms of meat or fish weekly and is entitled to GH¢60 a month for transport.

However, his demand for the payment of social security tickled nerves a few times and so he had to let go.

“I just want to save enough to return to school. So far, it has been good,” he said.

Source: Graphic.com.gh

(Selorm) |

(Selorm) |  (Nana Kwesi)

(Nana Kwesi)